My eyes haven’t been scrolling the social media platforms as much as I used to do a few years back. Partly because I don’t have the time anymore to do so in such frequency, and partly because many of my algorithms have become a cesspool of negativity and hate. Having said that, something I tend to follow is the way how teams play. And, I think, it comes as no surprise when I say that relationism as a style of play has been wandering around many feeds.

I’m not going to pretend I’m the expert on the coaching aspect of it and how to implement it. Neither do I think this article is going to bring forth groundbreaking results or theories. My aim with this article is to use event data to identify teams that are hybrid positional-relational or have a strong dominance of relationism in their style of play. Is it something that can only be captured by the eye and by a stroke of culture/emotion? Or can we use event data to recognise patterns and find teams that play that way?

Contents

- Why use event data to try and capture the playing style?

- Theoretical Framework

- Data & Methodology

- Results

- Final thoughts

Why use event data to try and capture the playing style?

Football, at its essence, is a living tapestry of player interactions constantly evolving around the central object of desire: the ball. As players move and respond to one another, distinct patterns emerge in their collective actions, particularly visible in the intricate networks formed through passing sequences.

Though traditional event data captures only moments when players directly engage with the ball, these touchpoints nonetheless reveal profound relational qualities. We can measure these qualities through various lenses: the diversity of passing choices (entropy), the formation of interconnected player clusters, and the spatial coordination that emerges as players position themselves in relation to teammates.

This approach to understanding football resonates deeply with relationist philosophy. From this perspective, the game’s meaning doesn’t reside in static positions or isolated actions, but rather in the dynamic, ever-shifting relationships between players as the match unfolds. What matters is not where individual players stand, but how they move and interact relative to one another, creating a fluid system of meaning that continuously transforms throughout the ninety minutes.

Theoretical Framework

Football style through a relationist lens isn’t defined by predetermined positions but emerges organically from player interactions. This approach, which is founded on spontaneity, spatial intelligence, and fluid connectivity, stands in contrast to positional play’s structured framework of designated zones and tactical discipline.

In relational systems, players coordinate through intuitive responses to teammates, opponents, and the ball’s context. The tactical framework materialises through the play itself rather than being imposed beforehand.

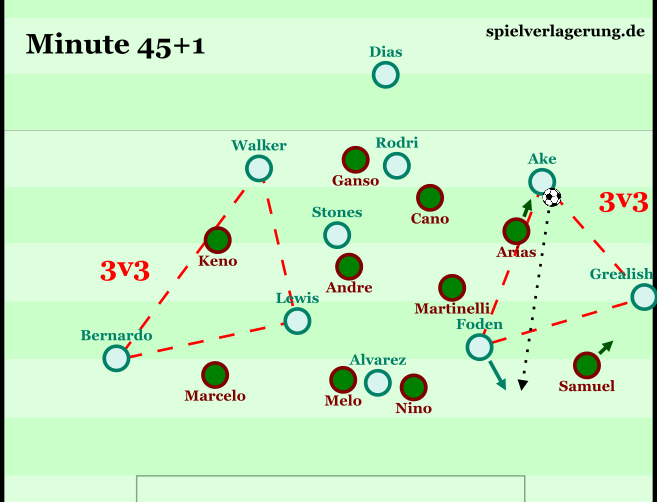

On the pitch, this manifests as continuously reforming passing triangles, compact and diverse passes, constant support near the ball, and freedom from positional constraints. Players gravitate toward the ball, creating local numerical advantages and dynamic combinations. Creative responsibility is distributed, shifting naturally with each possession phase, while team structure becomes fluid and contextual, adapting to the evolving match situation.

Analytically, traditional metrics like zone occupation or average positions presume stability and structure that relational play defies. Effective analysis requires shifting from static measurements to interaction-based indicators.

This research introduces metrics derived from event data corresponding to relational principles: clustering coefficients quantify local interaction density, pass entropy measures improvisational variety, and support the proximity index tracks teammate closeness to the ball, enabling dynamic identification of relational phases throughout matches.

Data and methodology

This study uses a quantitative methodology to identify and measure relational play in football through structured event data. The dataset includes match records from the 2024–25 Eredivisie Women’s league. Each event log contains details such as player and team identifiers, event type (e.g. pass, duel, shot), spatial coordinates (x and y values on a normalised 100×68 pitch), and timestamp. Only pass events are used in the analysis, since passing is the most frequent and structurally revealing action in football. The data comes from Opta/StatsPerform and was collected on May 1st, 2025, for the Dutch Eredivisie Women.

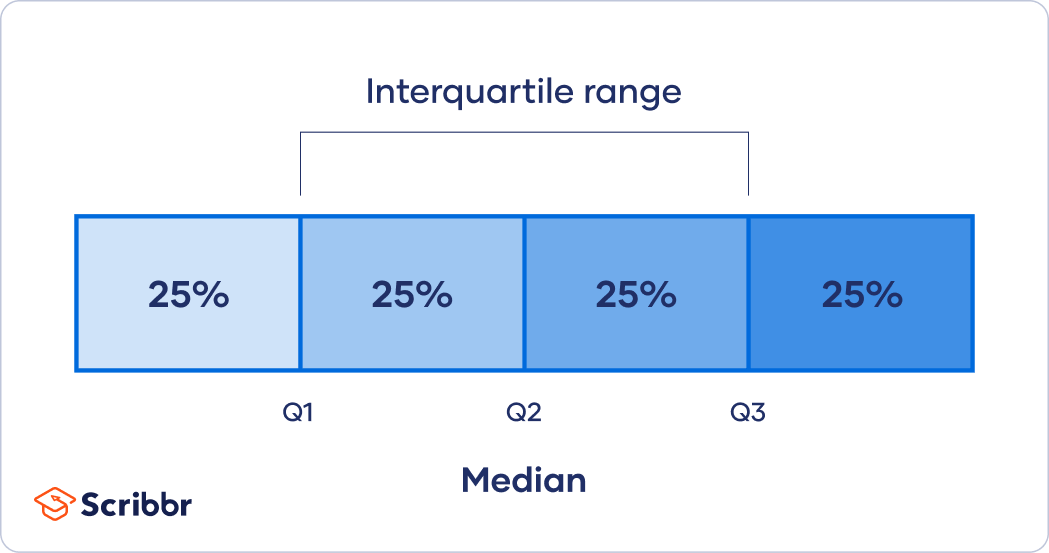

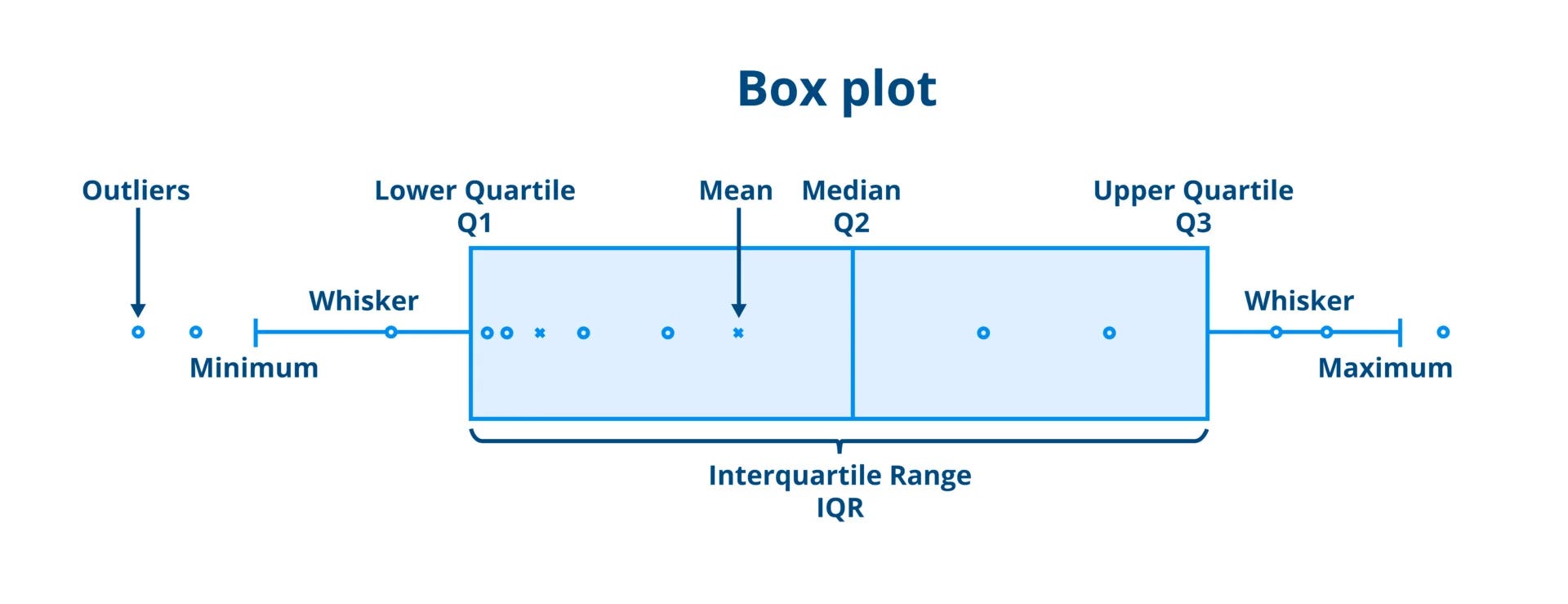

To capture long-term relational behaviour, each match is segmented into 45-minute windows. Each window is treated independently and analysed for signs of relational play using three custom-built metrics:

- Clustering Coefficient measures triangle formation frequency in passing networks, where players are nodes and passes are directed edges. A player’s coefficient is calculated by dividing their actual triangle involvement by their potential maximum. The team’s average value indicates local connectivity density—a fundamental characteristic of relational play.

- Pass Entropy quantifies passing variety. By calculating the probability distribution of each player’s passes to teammates, we derive their Shannon entropy score. Higher entropy indicates more diverse passing choices, reflecting improvisational play rather than predictable patterns. The team value averages individual entropies, excluding players with minimal passing involvement.

- Support Proximity Index evaluates teammate availability. For each pass, we count teammates within a 15-meter radius of the passer. The average across all passes reveals how consistently the team maintains close support around the ball—a defining principle of relational football that enables spontaneous combinations and fluid progression.

To combine these three metrics into one unified measure, we normalise each one using min-max scaling so they fall between 0 and 1. The resulting Relational Index (RI) is then calculated using the formula:

RI = 0.4 × Clustering + 0.3 × Proximity + 0.3 × Entropy

These weights reflect the greater theoretical importance of triangle-based interaction (clustering), followed by support around the ball and variability in pass choices.

A window is labelled as relational if its RI exceeds 0.5. For each team in each match, we compute the percentage of their 2-minute windows that meet this criterion. This gives us the team’s Relational Time Percentage, which acts as a proxy for how often the team plays relationally during a match. When averaged across multiple matches, this percentage becomes a stable tactical signature of that team’s playing style.

Results

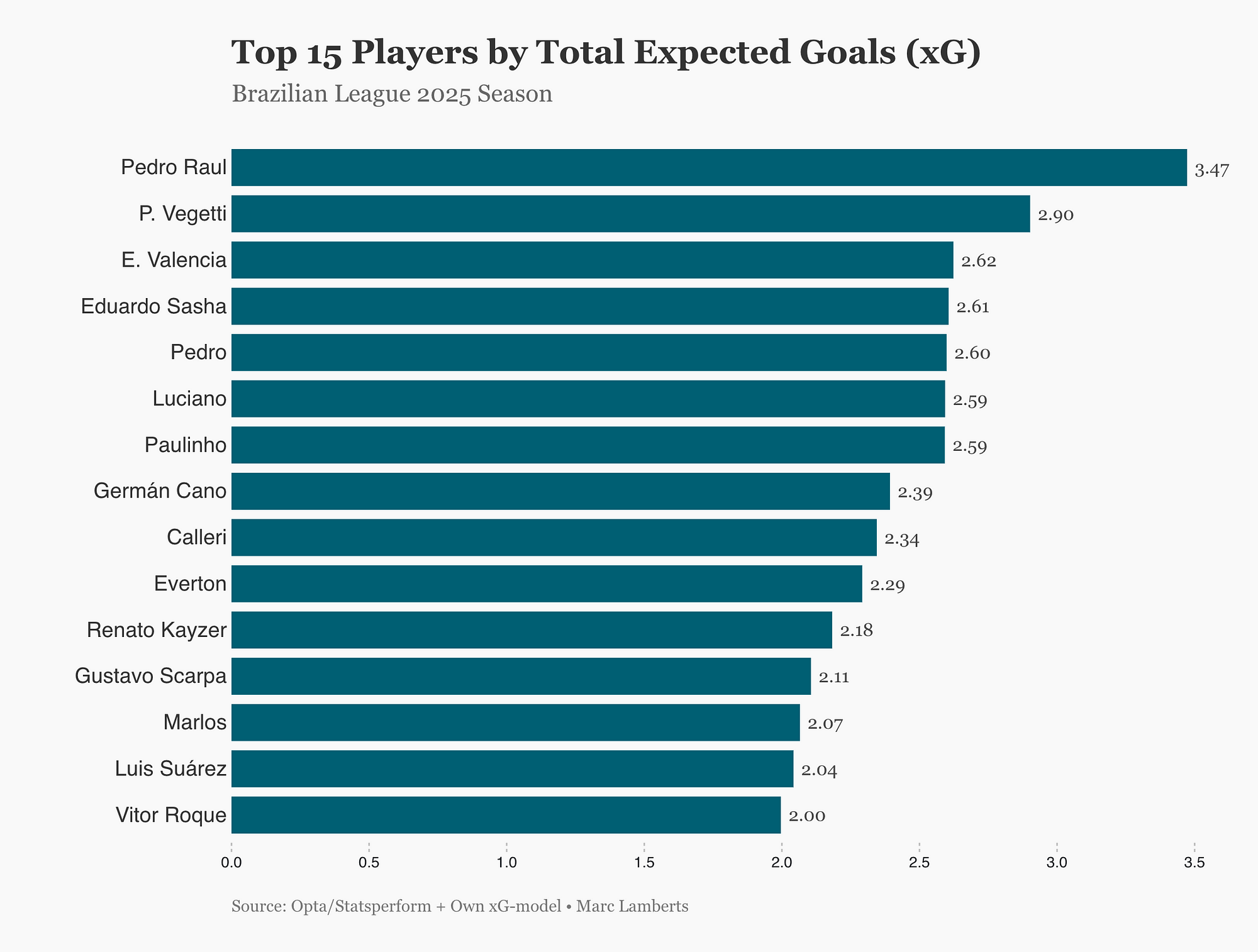

Applying the relational framework to matches from the 2024–25 Eredivisie Women’s league revealed that relational play, as defined by the Relational Index (RI), occurs infrequently but measurably. Using 45-minute windows and a threshold of RI > 0.5, most teams displayed relational behaviour in less than 10% of total match time.

Across all matches analysed, the league-wide average was 8.3%, with few teams exceeding 15%. Based on these distributions, the study proposes classification thresholds: below 10% as “structured,” 10–25% as “relational tendencies,” and above 25% as “highly relational.” Visual inspections of high-RI segments showed dense passing networks, triangular combinations, and compact support near the ball, consistent with tactical descriptions of relational football.

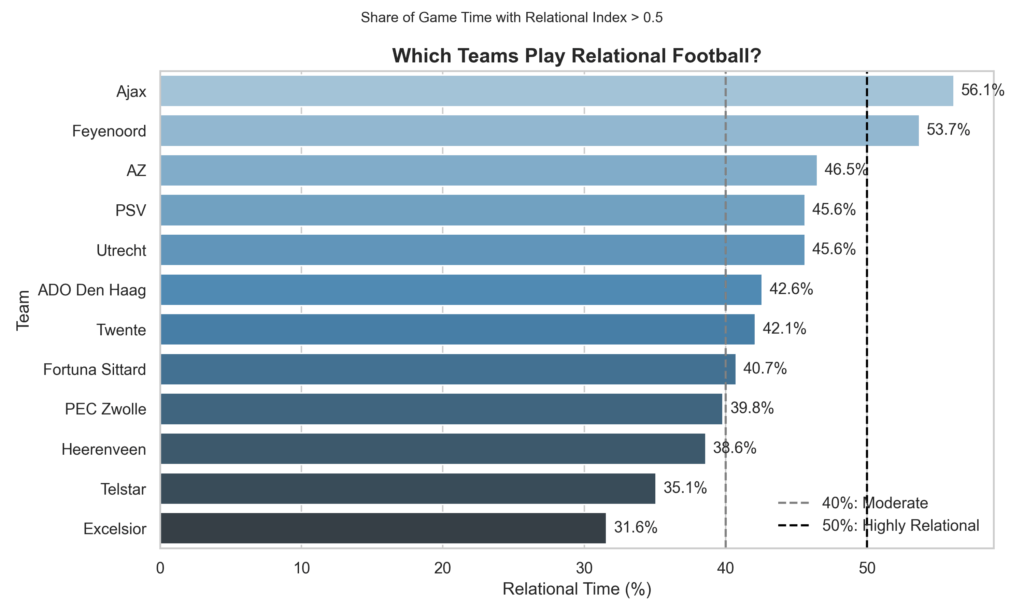

In the bar chart above we can see the Eredivisie Women 2024-2025 teams and how relational their style of play is. It measures how much of the time they have played in relational principles. I have two thresholds:

- 40% is the threshold for moderate relationism in football and those teams can be said to play relationism in their football or a hybrid style that favours relationism

- 50% is highly relationism. From that percentage we can say a team is truly relationism in their style of play.

Now as you can see there are quite some teams that are moderate, but truly relationism is only played – according to this data – by Ajax and Feyenoord.

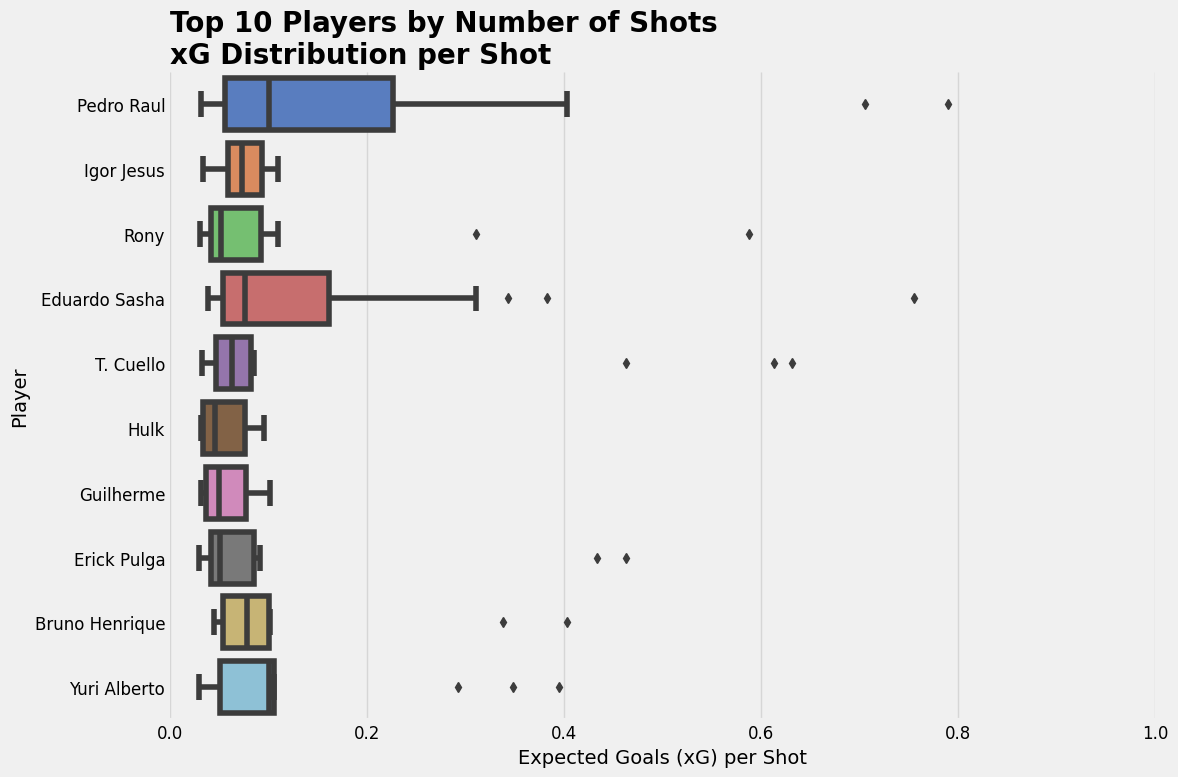

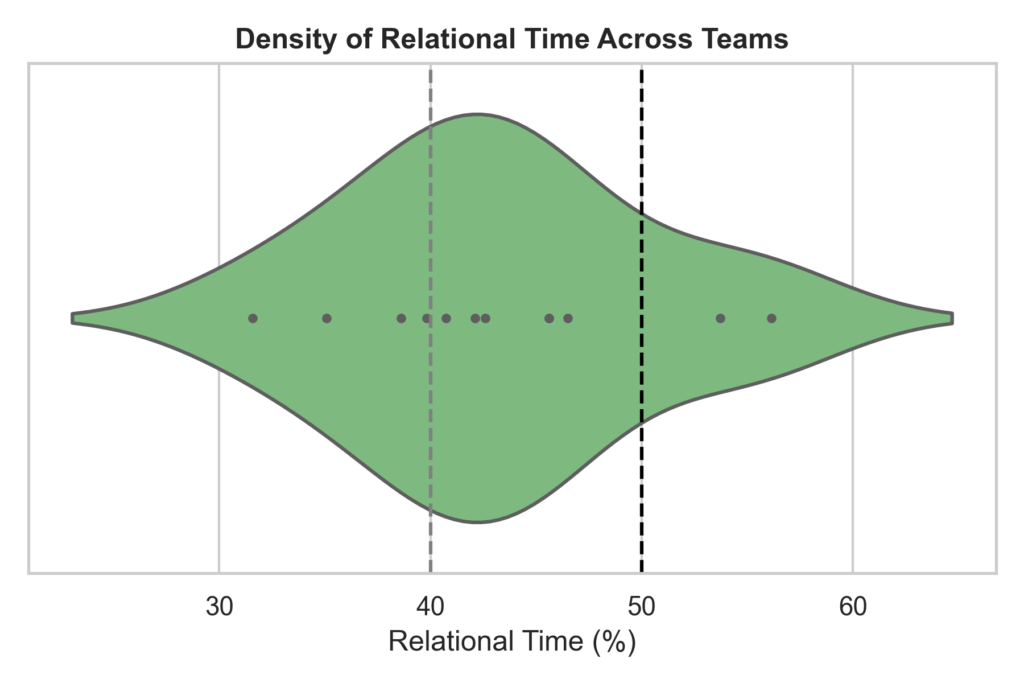

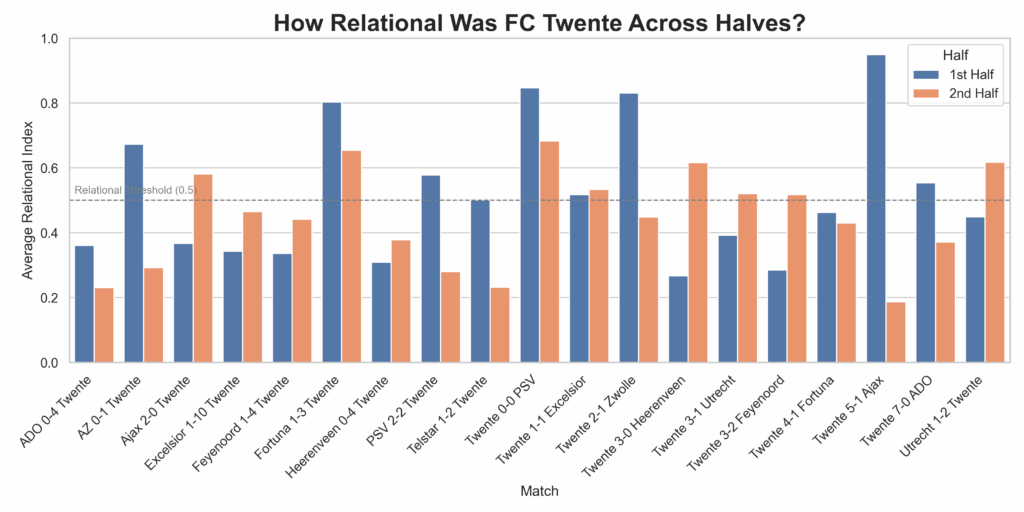

As you can see this in this violin plot, most of the time are in the moderate threshold, meaning that they have tendencies of relationism in their play, but not fully there. Now, if we look at one team we can see something different on how they play throughout the season. We are going with FC Twente, which is the best team of the season and arguably the best team of the past decade.

This grouped bar chart visualises FC Twente’s average Relational Index in the first and second halves of each match, using a 0.5 threshold to indicate relational play. By comparing the two bars per match, we can see whether Twente sustains, increases, or declines in relational behavior after halftime. The visualisation reveals how tactical fluidity evolves throughout matches, highlighting consistency or contrast between halves. Matches where both bars are above 0.5 suggest sustained relational intent, while large gaps may indicate halftime adjustments or fatigue. This provides insight into Twente’s game management and stylistic adherence across different phases of play.

Final thoughts

This study demonstrates that relational football—a style characterised by adaptive coordination, dense passing, and ball-near support—can be meaningfully identified using structured event data. Through a composite Relational Index, short relational phases were detected across matches, though their overall frequency was low, suggesting such play is rare or context-dependent. The model proved sensitive to fluctuations in team behaviour, offering a new lens for analysing tactical identity and match dynamics.

However, limitations include reliance on on-ball data, which excludes off-ball positioning, and the use of fixed two-minute windows that may overlook brief relational episodes. Additionally, the index’s threshold and normalisation methods, while effective, introduce subjectivity and restrict cross-match comparison. The current framework also lacks contextual variables like scoreline or pressing intensity. Despite these constraints, the findings support the claim that relational football, though abstract, leaves identifiable statistical traces, offering a scalable method for tactical profiling and a foundation for future model refinement.